TALKS AND CONFERENCES

Upcoming Presentations

8-10 March 2024

Conference: Seventh International Bagpipe Conference

Academy of Music, Dance, and Fine Arts, Plovdiv, Bulgaria

Presentation title: The Metropolitan Museum’s Bagpipe Collection: Aesthetics, Materials, and Symbolism

Abstract

The Metropolitan Museum hosts a collection of 52 bagpipes from around the world. Collected mainly by Mary Elizabeth Brown at the turn of the 19th century, these span a large geographical area, from India to Ireland, Russia to Libya. The instruments are made from a wide range of materials such as hide, wood, metal and reed, that are not only functional but also highly aestheticized and imbued with symbolical meaning. Consider the finely carved goat head with miniature ivory teeth on a 19th century Central French musette, a bejeweled square cross and tiny metallic bird ornaments on an old Russian volynka, small human features that anthropomorphize the Croatian diple, and grotesque dolphin heads on the stock of a French 19th century fantasy bagpipe - reminiscent of the coat of arms of pre-revolution French princes -, as well as the use of tassels, satin, ribbons, ivory, engravings, lead incrustations and even decalcomania on many other instruments.

This presentation will open with an introduction to the collection, providing a brief summary of how the instruments came to the collection. I will then examine specific examples of how instruments merge functional materials (such as animal hide, textile, horns, and rope) and shapes (such as stocks, chanters and drones) with aesthetics and symbolism. This includes forays into the realms of the animal kingdom, religion, superstition and exoticism as well as into the social mobility and musical function of some of these instruments. This paper is the outcome of a Chester Dale Fellowship at the Metropolitan Museum.

Conference: Seventh International Bagpipe Conference

Academy of Music, Dance, and Fine Arts, Plovdiv, Bulgaria

Presentation title: The Metropolitan Museum’s Bagpipe Collection: Aesthetics, Materials, and Symbolism

Abstract

The Metropolitan Museum hosts a collection of 52 bagpipes from around the world. Collected mainly by Mary Elizabeth Brown at the turn of the 19th century, these span a large geographical area, from India to Ireland, Russia to Libya. The instruments are made from a wide range of materials such as hide, wood, metal and reed, that are not only functional but also highly aestheticized and imbued with symbolical meaning. Consider the finely carved goat head with miniature ivory teeth on a 19th century Central French musette, a bejeweled square cross and tiny metallic bird ornaments on an old Russian volynka, small human features that anthropomorphize the Croatian diple, and grotesque dolphin heads on the stock of a French 19th century fantasy bagpipe - reminiscent of the coat of arms of pre-revolution French princes -, as well as the use of tassels, satin, ribbons, ivory, engravings, lead incrustations and even decalcomania on many other instruments.

This presentation will open with an introduction to the collection, providing a brief summary of how the instruments came to the collection. I will then examine specific examples of how instruments merge functional materials (such as animal hide, textile, horns, and rope) and shapes (such as stocks, chanters and drones) with aesthetics and symbolism. This includes forays into the realms of the animal kingdom, religion, superstition and exoticism as well as into the social mobility and musical function of some of these instruments. This paper is the outcome of a Chester Dale Fellowship at the Metropolitan Museum.

27-30 June 2024

Conference: American Musical Instrument Society, Annual Conference

Musical Instrument Museum, Phoenix, USA

Presentation title: The sruti upanga: the drone of the devadasi

Abstract

The sruti upanga is a mysterious instrument. It is a simple bagpipe, composed of an animal bag, an insufflation pipe and a pipe with six or seven holes. Mostly extinct today, especially in Tamil Nadur (Southern India) where it was historically most played, it is ubiquitous in iconography from the late 18th century until the early 20th century. There, amongst other musicians and dancers, one can regularly spot a man playing this instrument. The sruti upanga was one of the instruments played by male musicians to accompany the devadasi, hereditary female devotional dancers and singers. Despite the instrument’s regular appearance in a wide variety of paintings and its presence in some photographic material, only very few examples of the instrument exist in musical collections. The Metropolitan Museum in New York (USA) and the Pitt Rivers Museum in Oxford (UK) hold two well-preserved examples. Other than its mention in a handful of historical sources, this instrument is absent from organological and musicological literature.

This paper will shed light on what seems to be a mostly extinct instrument. Led by archival research, organological observations, and the analysis of the only known video of the instrument, I will describe the instrument and its musical role. I will define the social role of the musicians and performers around this instrument, and put forward a theory as to its extinction in the 1930s and 1940s. Based on the analysis of musical drones in carnatic music as well as the playing technique of the instrument, I will suggest what the instrument’s musical influence might have been on Southern Indian carnatic music.

Conference: American Musical Instrument Society, Annual Conference

Musical Instrument Museum, Phoenix, USA

Presentation title: The sruti upanga: the drone of the devadasi

Abstract

The sruti upanga is a mysterious instrument. It is a simple bagpipe, composed of an animal bag, an insufflation pipe and a pipe with six or seven holes. Mostly extinct today, especially in Tamil Nadur (Southern India) where it was historically most played, it is ubiquitous in iconography from the late 18th century until the early 20th century. There, amongst other musicians and dancers, one can regularly spot a man playing this instrument. The sruti upanga was one of the instruments played by male musicians to accompany the devadasi, hereditary female devotional dancers and singers. Despite the instrument’s regular appearance in a wide variety of paintings and its presence in some photographic material, only very few examples of the instrument exist in musical collections. The Metropolitan Museum in New York (USA) and the Pitt Rivers Museum in Oxford (UK) hold two well-preserved examples. Other than its mention in a handful of historical sources, this instrument is absent from organological and musicological literature.

This paper will shed light on what seems to be a mostly extinct instrument. Led by archival research, organological observations, and the analysis of the only known video of the instrument, I will describe the instrument and its musical role. I will define the social role of the musicians and performers around this instrument, and put forward a theory as to its extinction in the 1930s and 1940s. Based on the analysis of musical drones in carnatic music as well as the playing technique of the instrument, I will suggest what the instrument’s musical influence might have been on Southern Indian carnatic music.

27-30 June 2024

Conference: The Materiality and Meaning of Musical Instruments, Galpin Society

Oxford University, Bates Museum

Presentation title: From Cairo to Marrakesh: Nineteenth century historical accounts of African bagpipes

Abstract

At last, carts, baggage and escort, with the women and children, surrounded by a singing, yelling crowd of excited friends and relatives, with many drums and bagpipes, and all the rag, tag, and bobtail of Tripoli, rolled out through the narrow roads to the first camping-place (Vischer, 1910:22)

In 1910, Hanns Vischer (1876-1945) published his account of a caravan journey Across the Sahara desert from Tripoli to Bornu. Vischer was an education adviser to the government of the Northern Nigeria Protectorate for the British colonial service. His knowledge of Arabic, Hausa, Fulani and Kanuri meant that his account of a journey from Tripli to Bornu, following historical slave trade routes, was full of reported conversations and anthropological observations, bringing to life the people he travelled with. In this volume, Vischer mentions the bagpipes regularly, making it one of the most vivid and socially accurate accounts of this instrument historically.

This presentation gives an overview of travel accounts from the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, providing new insights into the bagpipes of Northern Africa. From Egypt to Morocco, these sources supplement the tangible examples that are found in British and American collections, giving insight into local proactices, some of which seem to have disappeared. They also provide new information as to the reach of these instruments, who played them, and in which social situations. While contextualisting the accounts in their colonial and imperialist contexts, I offer here a first attempt at writing a history of the mizwid and zukra through historical texts written in French, Italian, and English.

Conference: The Materiality and Meaning of Musical Instruments, Galpin Society

Oxford University, Bates Museum

Presentation title: From Cairo to Marrakesh: Nineteenth century historical accounts of African bagpipes

Abstract

At last, carts, baggage and escort, with the women and children, surrounded by a singing, yelling crowd of excited friends and relatives, with many drums and bagpipes, and all the rag, tag, and bobtail of Tripoli, rolled out through the narrow roads to the first camping-place (Vischer, 1910:22)

In 1910, Hanns Vischer (1876-1945) published his account of a caravan journey Across the Sahara desert from Tripoli to Bornu. Vischer was an education adviser to the government of the Northern Nigeria Protectorate for the British colonial service. His knowledge of Arabic, Hausa, Fulani and Kanuri meant that his account of a journey from Tripli to Bornu, following historical slave trade routes, was full of reported conversations and anthropological observations, bringing to life the people he travelled with. In this volume, Vischer mentions the bagpipes regularly, making it one of the most vivid and socially accurate accounts of this instrument historically.

This presentation gives an overview of travel accounts from the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, providing new insights into the bagpipes of Northern Africa. From Egypt to Morocco, these sources supplement the tangible examples that are found in British and American collections, giving insight into local proactices, some of which seem to have disappeared. They also provide new information as to the reach of these instruments, who played them, and in which social situations. While contextualisting the accounts in their colonial and imperialist contexts, I offer here a first attempt at writing a history of the mizwid and zukra through historical texts written in French, Italian, and English.

5-7 July 2024

Conference: Mahillon and his time

Musée des Instruments de Musique, Brussels, Belgium

Presentation title: Mary Elizabeth Brown’s Global Network: A case study of the Metropolitan Museum’s bagpipe collection

Abstract

Mary Elizabeth Brown was an avid musical instrument collector. After donating her first 270 musical instruments to the Metropolitan Museum of Art in 1889, effectively consolidating the place of musical instruments within the institution, and assigning herself as the curator of the collection, she worked with contacts across the world to grow the collection.

Brown had a strong interest in bagpipes if one is to judge by the museum’s healthy collection. By 1908, the musical instrument department counted 38 bagpipes from across the world. Brown frequently called upon her extensive network to seek out specific instruments. Her pursuit of a French bagpipe, for example, was strong enough for her to write to Victor-Charles Mahillon, the curator of the musical instruments collection at Brussels’ Royal Music Conservatoire. On 30th May 1894, she asked: ‘Would it be possible to get a Musette (French bagpipe) for I have none in my collection?’ (Letter Brown to Mahillon, MetMuseum archives). Mahillon was already a close acquaitance, and they had met in person when Brown visited Brussels not long before. Mahillon became a key ally in building the collection: he shipped over new instruments, but also identified desirable pieces and put her in contact with other European collectors and sellers.

One of the strengths of Mary Elizabeth Brown’s collection is that she accepted all sorts of music-making items. She collected instruments that her contemporaries barely considered a musical object. As such, some objects in the collection are rare witnesses of music that has since disappeared, or that has drastically changed over the last 120 years. This is the case of the Indian sruti upanga bagpipe, which is mostly extinct today. In other instances, the Met holds some of the oldest examples of instruments still played today, such as the Met Museum’s Maltese Zaqq, which is a rare historical example of the instrument (Borg Cardona 2020).

In this paper, I will focus on how Mary Elizabth Brown collected the widely different thirty-eight bagpipes that are now held in New York. Coming from places such as India, Egypt, France, Greece, Turkey, and the UK, she relied on friends, commercial partners, and government officials to scout, purchase, and send them to New York. By examining her correspondence and the material evidence at hand, I will contextualise Brown’s collecting practice and trace the international routes that brought these instruments to one of the most prominent insrument collections of the world.

Conference: Mahillon and his time

Musée des Instruments de Musique, Brussels, Belgium

Presentation title: Mary Elizabeth Brown’s Global Network: A case study of the Metropolitan Museum’s bagpipe collection

Abstract

Mary Elizabeth Brown was an avid musical instrument collector. After donating her first 270 musical instruments to the Metropolitan Museum of Art in 1889, effectively consolidating the place of musical instruments within the institution, and assigning herself as the curator of the collection, she worked with contacts across the world to grow the collection.

Brown had a strong interest in bagpipes if one is to judge by the museum’s healthy collection. By 1908, the musical instrument department counted 38 bagpipes from across the world. Brown frequently called upon her extensive network to seek out specific instruments. Her pursuit of a French bagpipe, for example, was strong enough for her to write to Victor-Charles Mahillon, the curator of the musical instruments collection at Brussels’ Royal Music Conservatoire. On 30th May 1894, she asked: ‘Would it be possible to get a Musette (French bagpipe) for I have none in my collection?’ (Letter Brown to Mahillon, MetMuseum archives). Mahillon was already a close acquaitance, and they had met in person when Brown visited Brussels not long before. Mahillon became a key ally in building the collection: he shipped over new instruments, but also identified desirable pieces and put her in contact with other European collectors and sellers.

One of the strengths of Mary Elizabeth Brown’s collection is that she accepted all sorts of music-making items. She collected instruments that her contemporaries barely considered a musical object. As such, some objects in the collection are rare witnesses of music that has since disappeared, or that has drastically changed over the last 120 years. This is the case of the Indian sruti upanga bagpipe, which is mostly extinct today. In other instances, the Met holds some of the oldest examples of instruments still played today, such as the Met Museum’s Maltese Zaqq, which is a rare historical example of the instrument (Borg Cardona 2020).

In this paper, I will focus on how Mary Elizabth Brown collected the widely different thirty-eight bagpipes that are now held in New York. Coming from places such as India, Egypt, France, Greece, Turkey, and the UK, she relied on friends, commercial partners, and government officials to scout, purchase, and send them to New York. By examining her correspondence and the material evidence at hand, I will contextualise Brown’s collecting practice and trace the international routes that brought these instruments to one of the most prominent insrument collections of the world.

Past Events

|

28 November 2023 (Première)

Don't Mind If I Don't - Pilot Episode Blurb: In this inaugural episode of Don't Mind If I Don't, actor/comedian Aaron Gold tries to see the merits of bagpipes. Will his horizons be expanded? Or if someone wants a cacophony of honking, should they just do what normal people do and tape a bunch of geese together? He interviews bagpipe expert Dr Cassandre Balosso-Bardin and piper John Henderson to find out more... Hosts: Aaron Gold and Christine Stoddard Director: Tom Dunn Special Guests: Cassandre Balbar, International Bagpipe Organization John Henderson, NYU & King's County Pipes & Drums Band Director of Photography/Editor: Jacob Maximilian Baron Line Producer: Bridget Dennin Production Assistant: Betsy Ramazzini Filmed on location at Manhattan Neighborhood Network (MNN) in New York City. |

|

|

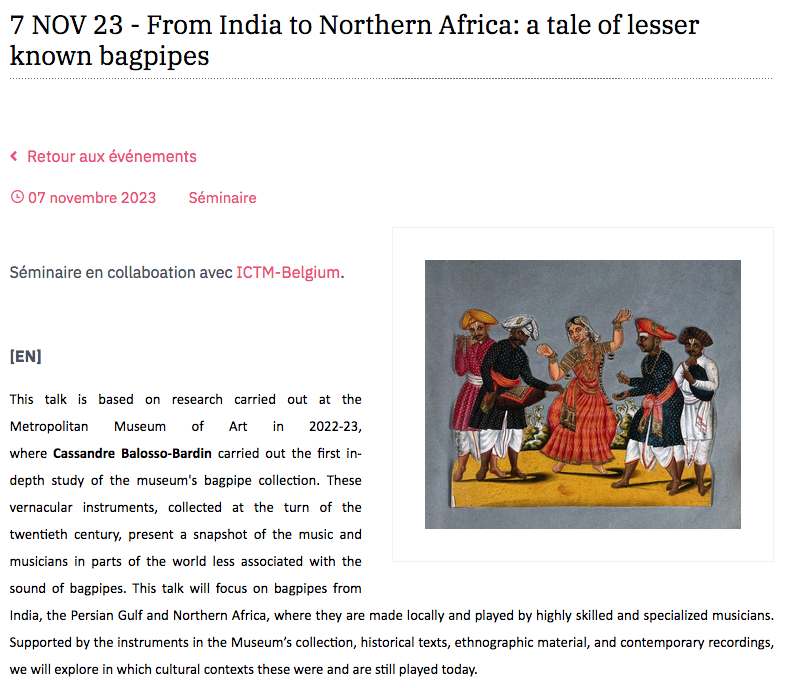

7 November 2023

Université Libre de Bruxelles, Seminar Series Presentation title: From India to Nothern Africa: a tale of lesser-known bagpipes Abstract This talk is based on research carried out at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in 2022-23, where Cassandre Balosso-Bardin carried out the first in-depth study of the museum's bagpipe collection. These vernacular instruments, collected at the turn of the twentieth century, present a snapshot of the music and musicians in parts of the world less associated with the sound of bagpipes. This talk will focus on bagpipes from India, the Persian Gulf and Northern Africa, where they are made locally and played by highly skilled and specialized musicians. Supported by the instruments in the Museum’s collection, historical texts, ethnographic material, and contemporary recordings, we will explore in which cultural contexts these were and are still played today. |

31 May-3 June 2023

Conference: American Musical Instrument Society's Annual Meeting

Rudi E. Scheidt School of Music at the University of Memphis, USA

Presentation title: The Metropolitan Museum’s Bagpipe Collection: Aesthetics, Materials, and Symbolism

Abstract

The Metropolitan Museum hosts a collection of 53 bagpipes from around the world. Collected mainly by Mary Elizabeth Brown at the turn of the 19th century, these span a large geographical area, from India to Ireland, Russia to Libya. The instruments are made from a wide range of materials such as hide, wood, metal and reed, that are not only functional but also highly aestheticized and imbued with symbolical meaning. Consider the finely carved goat head with miniature ivory teeth on a 19th century Central French musette, a bejeweled square cross and tiny metallic bird ornaments on an old Russian volynka, small human features that anthropomorphize the Croatian diple, and grotesque dolphin heads on the stock of a French 19th century fantasy bagpipe - reminiscent of the coat of arms of pre-revolution French princes -, as well as the use of tassels, satin, ribbons, ivory, engravings, lead incrustations and even decalcomania on many other instruments.

This presentation will open with an introduction to the collection, providing a brief summary of how the instruments came to the collection. I will then examine specific examples of how instruments merge functional materials (such as animal hide, textile, horns, and rope) and shapes (such as stocks, chanters and drones) with aesthetics and symbolism. This includes forays into the realms of the animal kingdom, religion, superstition and exoticism as well as into the social mobility and musical function of some of these instruments. This paper is the outcome of a Chester Dale Fellowship at the Metropolitan Museum.

Conference: American Musical Instrument Society's Annual Meeting

Rudi E. Scheidt School of Music at the University of Memphis, USA

Presentation title: The Metropolitan Museum’s Bagpipe Collection: Aesthetics, Materials, and Symbolism

Abstract

The Metropolitan Museum hosts a collection of 53 bagpipes from around the world. Collected mainly by Mary Elizabeth Brown at the turn of the 19th century, these span a large geographical area, from India to Ireland, Russia to Libya. The instruments are made from a wide range of materials such as hide, wood, metal and reed, that are not only functional but also highly aestheticized and imbued with symbolical meaning. Consider the finely carved goat head with miniature ivory teeth on a 19th century Central French musette, a bejeweled square cross and tiny metallic bird ornaments on an old Russian volynka, small human features that anthropomorphize the Croatian diple, and grotesque dolphin heads on the stock of a French 19th century fantasy bagpipe - reminiscent of the coat of arms of pre-revolution French princes -, as well as the use of tassels, satin, ribbons, ivory, engravings, lead incrustations and even decalcomania on many other instruments.

This presentation will open with an introduction to the collection, providing a brief summary of how the instruments came to the collection. I will then examine specific examples of how instruments merge functional materials (such as animal hide, textile, horns, and rope) and shapes (such as stocks, chanters and drones) with aesthetics and symbolism. This includes forays into the realms of the animal kingdom, religion, superstition and exoticism as well as into the social mobility and musical function of some of these instruments. This paper is the outcome of a Chester Dale Fellowship at the Metropolitan Museum.

|

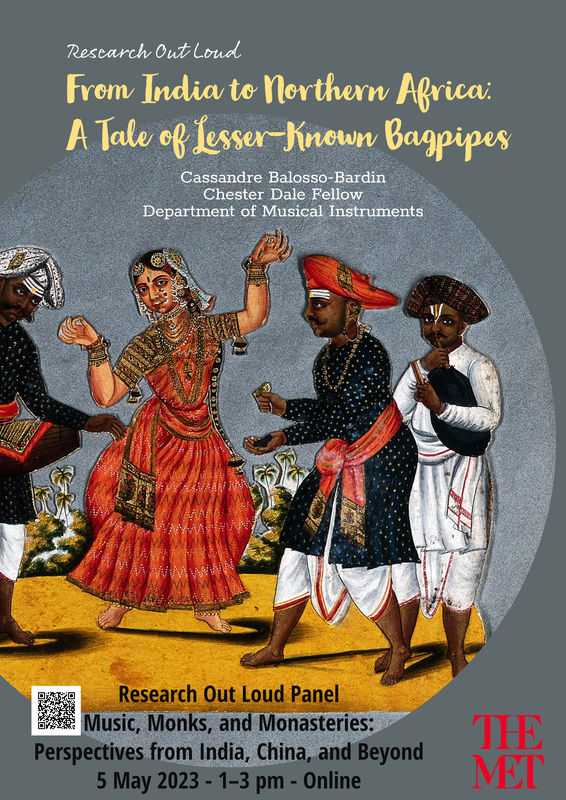

5 May 2023

Event: Research Out Loud (FREE ONLINE event) Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, USA Presentation Title: From India to Northern Africa: a tale of lesser-known bagpipes Registration link Abstract Within the Met’s collection of 53 bagpipes sit four bagpipes from India and Northern Africa. These vernacular instruments, collected at the turn of the 20th century, show a snapshot of the music and musicians in a part of the world lesser associated to the sound of bagpipes. While the Met instruments are historical, bagpipes are still thriving in many of these places and are central to important cultural practices. This includes regions and countries such as in Rajasthan in India, Libya and Tunisia in Northern Africa, where instruments are made locally and played by highly skilled and specialized musicians. Supported by the instruments in the collection, historical texts, ethnographic material and contemporary recordings, this presentation will delve into the bagpipes of India, Arabia and Northern Africa. I will open by an examination of the material instruments, understanding how these are connected and are part of the same family of bagpipes, which extends from India all the way to the Mediterranean. I will then focus on specific instruments and explore the musical and cultural contexts in which they are played, often linked to religious practices such as Sufism in Northern Africa and Hinduism in Northern India. |

22 February 2023

Fellow's Talk

Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

Talk Title: War, Politics and Gentlemen Musicians: A journey throughout the British Isles and the Met's British Bagpipes.

Fellow's Talk

Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

Talk Title: War, Politics and Gentlemen Musicians: A journey throughout the British Isles and the Met's British Bagpipes.

8-9 April 2022

Conference: British Forum for Ethnomusicology Annual Conference

Open University, Milton Keynes

Paper Title: The Ordinary UK Musician: Introducing the Craft Work/Play Model

Co-authored with Dr Victoria Ellis, University of Lincoln

Abstract

The fruit of interdisciplinary collaboration between business and music studies, this paper introduces the ordinary working musician conceptualised through the intersection of the craftworker and the craftplayer. Drawing on business and (ethno)musicological and sociological studies, the authors use the notions of craft (Sennett 2008), work vs. play/professional vs. amateur (Tsioulakis 2020, Finnegan 2008) and entrepreneurship to propose a theoretical frame that understands the musician as a craftsperson with an immaterial output. The Craft Work/Play model introduces two different conceptualisations of the musical craftsperson, which operate on a continuum, oscillating between the craftworker and the craftplayer. These categories are identified through differing motivations ranging from the extrinsic (motivated by remuneration) and intrinsic (motivated by the activity itself) (Juniu et al. 1996). These, in turn, are carried out within community and cultural frames, and will be influenced by the individual’s own projection of the output. As such, the musician can become a craftworker or a craftplayer depending on their personal goals.Supported by interdisciplinary literature, thispaper will first outline the theoretical concepts at play, before introducing the theoretical model and detailing its different components. It will conclude with an opening on how this initial research may be continued.

Conference: British Forum for Ethnomusicology Annual Conference

Open University, Milton Keynes

Paper Title: The Ordinary UK Musician: Introducing the Craft Work/Play Model

Co-authored with Dr Victoria Ellis, University of Lincoln

Abstract

The fruit of interdisciplinary collaboration between business and music studies, this paper introduces the ordinary working musician conceptualised through the intersection of the craftworker and the craftplayer. Drawing on business and (ethno)musicological and sociological studies, the authors use the notions of craft (Sennett 2008), work vs. play/professional vs. amateur (Tsioulakis 2020, Finnegan 2008) and entrepreneurship to propose a theoretical frame that understands the musician as a craftsperson with an immaterial output. The Craft Work/Play model introduces two different conceptualisations of the musical craftsperson, which operate on a continuum, oscillating between the craftworker and the craftplayer. These categories are identified through differing motivations ranging from the extrinsic (motivated by remuneration) and intrinsic (motivated by the activity itself) (Juniu et al. 1996). These, in turn, are carried out within community and cultural frames, and will be influenced by the individual’s own projection of the output. As such, the musician can become a craftworker or a craftplayer depending on their personal goals.Supported by interdisciplinary literature, thispaper will first outline the theoretical concepts at play, before introducing the theoretical model and detailing its different components. It will conclude with an opening on how this initial research may be continued.

27-29 May 2021

Conference: Les cornemuses médiévales: organologie, facture, modes de jeu, fonctions. 3eme sessions d'archéo-musicologie expérimentale

Saint-Guilhem-le-Désert (34150), France

Paper Title: La cornemuse médiévale à Majorque

Abstract

Caché parmis une multitude d’autres instrumentistes, un ange joue de la cornemuse sur le Portal del Mirador, le portail sud de la Seu, la cathédrale de Palma de Majorque. Taillé à la fin du 14è siècle par Joan Morey, il joue une petite cornemuse sans bourdon, ressemblant fortement aux enluminures des Cantigas de Santa María.

La cornemuse est l’un des instruments porteurs de la culture Majorquine aujourd’hui. Jouée traditionellement en duo avec un joueur de flûte et tambour, la cornemuse est symbolise le monde rural; elle est instrument des bergers jusque dans les années 1970. En remontant les siècles, l’on s’aperçoit que ces instruments étaient en circulation sur l’île dés le XIVe siècle. L’iconographie soutiendrait même que le duo cornemuse/flûte et tambour était déjà en utilisation. La fonction de la cornemuse médiévale, cependant, diffère grandement de celle de l’instrument moderne et leur morphologie est également différente.

Cette communication présentera l’instrument médiéval à Majorque, en prêtant attention à la fois à l’organologie et au contexte social grâce à l’analyse de l’iconographie médiévale ainsi que des extraits d’archives. Elle mettra en évidence les ruptures sociologiques, organologiques et fonctionelles entre le monde médiéval et le monde contemporain, bien que ce premier soit mis en valeur aujourd’hui par des célébrations et des rituels, créant un lien avec le passé.

Ce travail est un extrait d’une recherche anthropologique autour des xeremies, la cornemuse contemporatine de Majorque.

Conference: Les cornemuses médiévales: organologie, facture, modes de jeu, fonctions. 3eme sessions d'archéo-musicologie expérimentale

Saint-Guilhem-le-Désert (34150), France

Paper Title: La cornemuse médiévale à Majorque

Abstract

Caché parmis une multitude d’autres instrumentistes, un ange joue de la cornemuse sur le Portal del Mirador, le portail sud de la Seu, la cathédrale de Palma de Majorque. Taillé à la fin du 14è siècle par Joan Morey, il joue une petite cornemuse sans bourdon, ressemblant fortement aux enluminures des Cantigas de Santa María.

La cornemuse est l’un des instruments porteurs de la culture Majorquine aujourd’hui. Jouée traditionellement en duo avec un joueur de flûte et tambour, la cornemuse est symbolise le monde rural; elle est instrument des bergers jusque dans les années 1970. En remontant les siècles, l’on s’aperçoit que ces instruments étaient en circulation sur l’île dés le XIVe siècle. L’iconographie soutiendrait même que le duo cornemuse/flûte et tambour était déjà en utilisation. La fonction de la cornemuse médiévale, cependant, diffère grandement de celle de l’instrument moderne et leur morphologie est également différente.

Cette communication présentera l’instrument médiéval à Majorque, en prêtant attention à la fois à l’organologie et au contexte social grâce à l’analyse de l’iconographie médiévale ainsi que des extraits d’archives. Elle mettra en évidence les ruptures sociologiques, organologiques et fonctionelles entre le monde médiéval et le monde contemporain, bien que ce premier soit mis en valeur aujourd’hui par des célébrations et des rituels, créant un lien avec le passé.

Ce travail est un extrait d’une recherche anthropologique autour des xeremies, la cornemuse contemporatine de Majorque.

April 2021

Conference: BFE Annual Conference - Music, Culture, Nature

Bath Spa University

Paper Title: The social production of a Mallorcan bagpipe bag: collaboration, technology, ecology and internationalisation.

Abstract

Through the cultural, social, ecological and technological description of the Mallorcan bagpipe bag, this article underlines the role of tangible objects in shaping intangible heritage. In line with Allen’s urge to use the material links between culture and nature to support cultural sustainability (2019, 56) and answering Dawe’s call for more ‘detailed in-the-field study’ to showcase how musical instruments, far from being inert and insignificant objects, are ‘entangled in webs of culture’ (Dawe 2003, 278), it highlights the highly social nature of the production of a musical instrument and underlines the role of instrument-making towards the sustainability of a musical culture.

Historically made from one-year-old goats, Mallorcan bagpipe bags went through different phases of innovation, from rubber and Goretex® bags to purposefully factory-made hybrid bags. At the core of these changes are the musicians and the instrument makers, working together to create an instrument that can meet increasing musical and technological demands whilst supporting the cultural and ecological relevance of the instrument. Together, these elements work towards sustaining the identity of the instrument, removed from the shepherding profession it was traditionally associated with but symbolising the island of Mallorca, its land, language and culture, through a revitalised and modernised practice.

With the bagpipe bag at its centre, this paper pulls together its social networks (musicians, instrument makers, product providers) and its ecology (from local ressources to synthetic materials), both marked by technological advancements and international influences to create an instrument with a musical, cultural and social identity.

Conference: BFE Annual Conference - Music, Culture, Nature

Bath Spa University

Paper Title: The social production of a Mallorcan bagpipe bag: collaboration, technology, ecology and internationalisation.

Abstract

Through the cultural, social, ecological and technological description of the Mallorcan bagpipe bag, this article underlines the role of tangible objects in shaping intangible heritage. In line with Allen’s urge to use the material links between culture and nature to support cultural sustainability (2019, 56) and answering Dawe’s call for more ‘detailed in-the-field study’ to showcase how musical instruments, far from being inert and insignificant objects, are ‘entangled in webs of culture’ (Dawe 2003, 278), it highlights the highly social nature of the production of a musical instrument and underlines the role of instrument-making towards the sustainability of a musical culture.

Historically made from one-year-old goats, Mallorcan bagpipe bags went through different phases of innovation, from rubber and Goretex® bags to purposefully factory-made hybrid bags. At the core of these changes are the musicians and the instrument makers, working together to create an instrument that can meet increasing musical and technological demands whilst supporting the cultural and ecological relevance of the instrument. Together, these elements work towards sustaining the identity of the instrument, removed from the shepherding profession it was traditionally associated with but symbolising the island of Mallorca, its land, language and culture, through a revitalised and modernised practice.

With the bagpipe bag at its centre, this paper pulls together its social networks (musicians, instrument makers, product providers) and its ecology (from local ressources to synthetic materials), both marked by technological advancements and international influences to create an instrument with a musical, cultural and social identity.

|

18 August 2020

Festival: Music Village 2020 Agios Lavrendios, Greece Presentation title: An introduction to bagpipes of the world Description A 40-minute presentation for the general public on the wide range of bagpipes around the world. This talk was prepared for the Music Village 2020 edition in Agios Lavrendios, Greece. |

|

24 June 2020

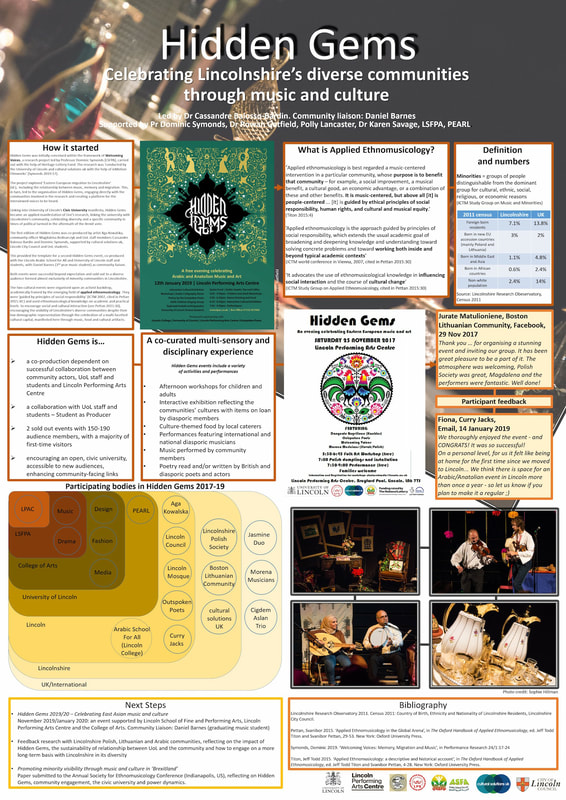

Conference: PEARL Conference 2020 University of Lincoln, UK Paper title: Hidden Gems: Celebrating Lincolnshire's minority communities Full presentation available on Youtube |

|

11-12 November 2019

Knowledge Frontiers Forum

Brisbane, Australia

The British Academy and the Australian Academy of the Humanities are jointly hosting a special event for humanities, arts and social science Early Career Researchers (ECRs) – the Knowledge Frontiers Forum on the ‘The Future’ – to take place Monday 11 and Tuesday 12 November 2019 in Brisbane.

This special event will bring together up to forty ECRs (understood as up to seven years after obtaining a PhD) from the UK, Australia and the Pacific region to discuss key questions around the futures theme.

This has been broadly envisaged, and areas of expected discussion include experiences of rapid social and cultural change, evolving notions of heritage, imaginations of the future, environmental futures, and co-designing and producing knowledge in the future.

Knowledge Frontiers Forum

Brisbane, Australia

The British Academy and the Australian Academy of the Humanities are jointly hosting a special event for humanities, arts and social science Early Career Researchers (ECRs) – the Knowledge Frontiers Forum on the ‘The Future’ – to take place Monday 11 and Tuesday 12 November 2019 in Brisbane.

This special event will bring together up to forty ECRs (understood as up to seven years after obtaining a PhD) from the UK, Australia and the Pacific region to discuss key questions around the futures theme.

This has been broadly envisaged, and areas of expected discussion include experiences of rapid social and cultural change, evolving notions of heritage, imaginations of the future, environmental futures, and co-designing and producing knowledge in the future.

7-10 November 2019

Conference: Society for Ethnomusicology annual conference

Bloomington, Indiana, USA

Paper Title: Promoting minority visibility through music and culture in 'Brexitland'

Abstract

Since 2017, University of Lincoln has invited a different local community each year to collaborate with the university's staff and students on a cultural and musical event, Hidden Gems. Initially organized through a research project reflecting on 'memory, migration and music' for Lincolnshire-based Eastern Europeans (Jones 2017), the event's unexpected sell-out success led university management to support and encourage following iterations, fitting in with the institution's civic engagement policy (Fazackerly 2018). The 2017 and 2019 events, organized with the help of Lincolnshire's Eastern European and Arabic communities respectively, used music and performance as a vector for empowerment, visibility and engagement to foster dialogue and awareness between non-UK and UK born populations. Particularly important in the current Brexit uncertainty and more so in Lincolnshire, the county with the highest percentage of Leave votes in 2016, this paper explores the importance of such events not only in the current political climate, but also in a largely low-paid, low-educated and mono-cultural environment (Lincolnshire Research Observatory 2001) where diversity is rarely celebrated on a wider scale. Through this case study, I will explore how universities can, partly through the application of ethnomusicological skills, influence their local environments by creating a welcoming platform for less visible minority groups. I will critically address the balance of power at play in the organization of such events as well as the limits of one-off events. Finally, I will discuss how the relationships created through these events can be sustained, to the mutual benefit of local and academic communities.

Conference: Society for Ethnomusicology annual conference

Bloomington, Indiana, USA

Paper Title: Promoting minority visibility through music and culture in 'Brexitland'

Abstract

Since 2017, University of Lincoln has invited a different local community each year to collaborate with the university's staff and students on a cultural and musical event, Hidden Gems. Initially organized through a research project reflecting on 'memory, migration and music' for Lincolnshire-based Eastern Europeans (Jones 2017), the event's unexpected sell-out success led university management to support and encourage following iterations, fitting in with the institution's civic engagement policy (Fazackerly 2018). The 2017 and 2019 events, organized with the help of Lincolnshire's Eastern European and Arabic communities respectively, used music and performance as a vector for empowerment, visibility and engagement to foster dialogue and awareness between non-UK and UK born populations. Particularly important in the current Brexit uncertainty and more so in Lincolnshire, the county with the highest percentage of Leave votes in 2016, this paper explores the importance of such events not only in the current political climate, but also in a largely low-paid, low-educated and mono-cultural environment (Lincolnshire Research Observatory 2001) where diversity is rarely celebrated on a wider scale. Through this case study, I will explore how universities can, partly through the application of ethnomusicological skills, influence their local environments by creating a welcoming platform for less visible minority groups. I will critically address the balance of power at play in the organization of such events as well as the limits of one-off events. Finally, I will discuss how the relationships created through these events can be sustained, to the mutual benefit of local and academic communities.

11-17 July 2019

Conference: 45th ICTM World Conference

Bangkok, Thailand

Panel: 'I'm a musician and a researcher': Four performers' approaches to practice-based research

Paper Title: ‘You are part of the club': Musicking in the field from a bagpiper's perspective

Abstract

Since Mantle Hood’s 1960 article on the concept of bi-musicality, it is common practice for ethnomusicologists to approach the field with musical practice in mind, considering it as an essential part of the participant-observation methodology. True bi-musicality, as described by Mantle Hood, is an asset, although I believe that only securing ‘basic musicianship’ (1960:58) within a given musical culture in order to be able to carry out sound musicological observations and analysis is not enough. Based on individual experiences in the European and Mediterranean bagpiping world, this paper explores how high-level musicianship and musical versatility has proven essential to access the internal social mechanisms surrounding music-making. Indeed, although access may seem like a basic element of fieldwork, easily attained through any level of music participation, I argue that musicking (in Small’s wider sense of the word) on the same level as local musicians, albeit not necessarily in the exact same tradition or style, forges a sense of belonging to a wider community of dedicated musicians and instrument makers and creates a space where respect, trust and musical intimacy are readily shared. Aside from facilitating dialogue, I argue that being seen as a ‘real’ musician has long-term implications in the field, including how it impacts research which, rather than being conceived as a separate activity, develops over time into an accepted and expected behaviour and becomes an integral part of the musicking experience both for the researcher and the musicians. Through this, the trust built by mutual understanding can lead musicians to entrust their voice to the researcher, as the latter will more readily be considered as ‘one of them’ and is therefore more likely to represent them respectfully internationally.

Conference: 45th ICTM World Conference

Bangkok, Thailand

Panel: 'I'm a musician and a researcher': Four performers' approaches to practice-based research

Paper Title: ‘You are part of the club': Musicking in the field from a bagpiper's perspective

Abstract

Since Mantle Hood’s 1960 article on the concept of bi-musicality, it is common practice for ethnomusicologists to approach the field with musical practice in mind, considering it as an essential part of the participant-observation methodology. True bi-musicality, as described by Mantle Hood, is an asset, although I believe that only securing ‘basic musicianship’ (1960:58) within a given musical culture in order to be able to carry out sound musicological observations and analysis is not enough. Based on individual experiences in the European and Mediterranean bagpiping world, this paper explores how high-level musicianship and musical versatility has proven essential to access the internal social mechanisms surrounding music-making. Indeed, although access may seem like a basic element of fieldwork, easily attained through any level of music participation, I argue that musicking (in Small’s wider sense of the word) on the same level as local musicians, albeit not necessarily in the exact same tradition or style, forges a sense of belonging to a wider community of dedicated musicians and instrument makers and creates a space where respect, trust and musical intimacy are readily shared. Aside from facilitating dialogue, I argue that being seen as a ‘real’ musician has long-term implications in the field, including how it impacts research which, rather than being conceived as a separate activity, develops over time into an accepted and expected behaviour and becomes an integral part of the musicking experience both for the researcher and the musicians. Through this, the trust built by mutual understanding can lead musicians to entrust their voice to the researcher, as the latter will more readily be considered as ‘one of them’ and is therefore more likely to represent them respectfully internationally.

11-14 April 2019

Conference: Collaborative Ethnomusicology - British Forum for Ethnomusicology annual conference

The Elphinstone Institute, University of Aberdeen, Scotland

Panel: 'I'm a musician and a researcher': Four performers' approaches to practice-based research

Paper Title: ‘You are part of the club': Musicking in the field from a bagpiper's perspective

Abstract

Since Mantle Hood’s 1960 article on the concept of bi-musicality, it is common practice for ethnomusicologists to approach the field with musical practice in mind, considering it as an essential part of the participant-observation methodology. True bi-musicality, as described by Mantle Hood, is an asset, although I believe that only securing ‘basic musicianship’ (1960:58) within a given musical culture in order to be able to carry out sound musicological observations and analysis is not enough. Based on individual experiences in the European and Mediterranean bagpiping world, this paper explores how high-level musicianship and musical versatility has proven essential to access the internal social mechanisms surrounding music-making. Indeed, although access may seem like a basic element of fieldwork, easily attained through any level of music participation, I argue that musicking (in Small’s wider sense of the word) on the same level as local musicians, albeit not necessarily in the exact same tradition or style, forges a sense of belonging to a wider community of dedicated musicians and instrument makers and creates a space where respect, trust and musical intimacy are readily shared. Aside from facilitating dialogue, I argue that being seen as a ‘real’ musician has long-term implications in the field, including how it impacts research which, rather than being conceived as a separate activity, develops over time into an accepted and expected behaviour and becomes an integral part of the musicking experience both for the researcher and the musicians. Through this, the trust built by mutual understanding can lead musicians to entrust their voice to the researcher, as the latter will more readily be considered as ‘one of them’ and is therefore more likely to represent them respectfully internationally.

Conference: Collaborative Ethnomusicology - British Forum for Ethnomusicology annual conference

The Elphinstone Institute, University of Aberdeen, Scotland

Panel: 'I'm a musician and a researcher': Four performers' approaches to practice-based research

Paper Title: ‘You are part of the club': Musicking in the field from a bagpiper's perspective

Abstract

Since Mantle Hood’s 1960 article on the concept of bi-musicality, it is common practice for ethnomusicologists to approach the field with musical practice in mind, considering it as an essential part of the participant-observation methodology. True bi-musicality, as described by Mantle Hood, is an asset, although I believe that only securing ‘basic musicianship’ (1960:58) within a given musical culture in order to be able to carry out sound musicological observations and analysis is not enough. Based on individual experiences in the European and Mediterranean bagpiping world, this paper explores how high-level musicianship and musical versatility has proven essential to access the internal social mechanisms surrounding music-making. Indeed, although access may seem like a basic element of fieldwork, easily attained through any level of music participation, I argue that musicking (in Small’s wider sense of the word) on the same level as local musicians, albeit not necessarily in the exact same tradition or style, forges a sense of belonging to a wider community of dedicated musicians and instrument makers and creates a space where respect, trust and musical intimacy are readily shared. Aside from facilitating dialogue, I argue that being seen as a ‘real’ musician has long-term implications in the field, including how it impacts research which, rather than being conceived as a separate activity, develops over time into an accepted and expected behaviour and becomes an integral part of the musicking experience both for the researcher and the musicians. Through this, the trust built by mutual understanding can lead musicians to entrust their voice to the researcher, as the latter will more readily be considered as ‘one of them’ and is therefore more likely to represent them respectfully internationally.

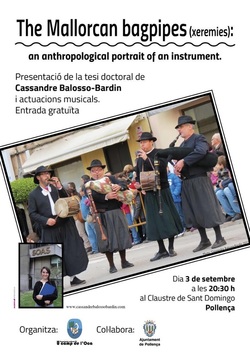

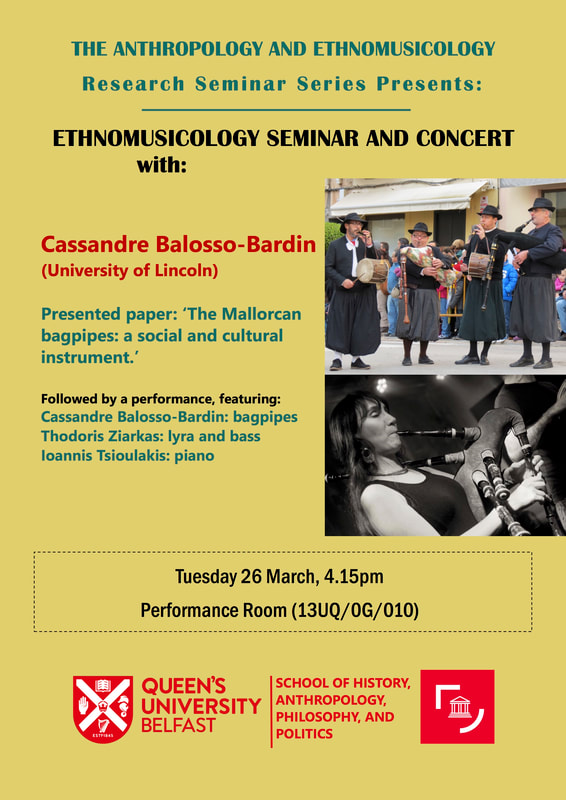

26 March 2019

Guest Lecture/Performance

Queen's University Belfast, Northern Ireland

Title: The Mallorcan bagpipes: a social and cultural instrument.

Performance with Ioannis Tsioulakis and Thodoris Ziarkas

Guest Lecture/Performance

Queen's University Belfast, Northern Ireland

Title: The Mallorcan bagpipes: a social and cultural instrument.

Performance with Ioannis Tsioulakis and Thodoris Ziarkas

20 March 2019

Conference: PEARL 2019 conference

University of Lincoln, UK

Poster: Hidden Gems: Celebrating Lincolnshire's diverse communities through music and culture

Conference: PEARL 2019 conference

University of Lincoln, UK

Poster: Hidden Gems: Celebrating Lincolnshire's diverse communities through music and culture

20 February 2019

Guest Lecture

Royal Holloway, University of London

Lecture title: Intercultural music making. Practical, social and creative issues

Guest Lecture

Royal Holloway, University of London

Lecture title: Intercultural music making. Practical, social and creative issues

7 November 2018

Guest Lecture

Bath Spa University

Lecture series: Intercultural Communication through Practice

Lecture title: Making music across borders: practical, logistical and musical issues.

Abstract

Using the international world music group Världens Band as a case study, this presentation will explore the issues faced by a band with a utopian goal of cross-border music making. These include not only the logistical practicalities of gathering musicians from different parts of the world to rehearse and play together, anchoring the group in a mobile and technological world, but also the delicate balance of the group whilst creating music and incorporating equal representation ideologies

Guest Lecture

Bath Spa University

Lecture series: Intercultural Communication through Practice

Lecture title: Making music across borders: practical, logistical and musical issues.

Abstract

Using the international world music group Världens Band as a case study, this presentation will explore the issues faced by a band with a utopian goal of cross-border music making. These include not only the logistical practicalities of gathering musicians from different parts of the world to rehearse and play together, anchoring the group in a mobile and technological world, but also the delicate balance of the group whilst creating music and incorporating equal representation ideologies

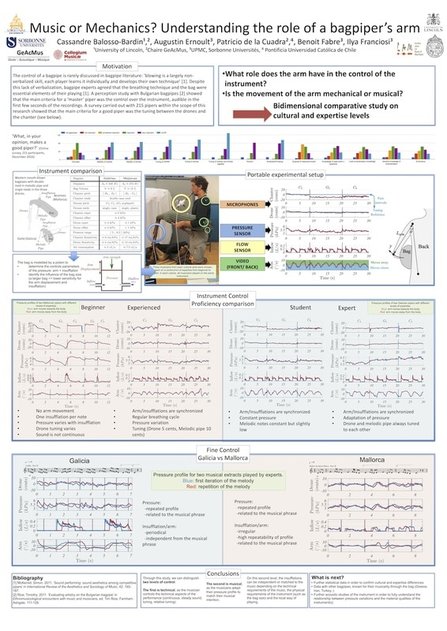

3 November 2018

Conference: First International Bulgarian Bagpipe Association Conference

Plovdiv Academy, Bulgaria

Paper Title: The bagpiper’s arm. Controlling the bag: a multidimensional study.

In this presentation, I endeavor to show how the bagpiper exerts control on his/her bag. Understanding this may enhance our comprehension of the importance of the arm in a musical context. Our main questions are: what role does the arm have in the control of the instrument? Is the bag controlled with musical intention? Leading from this, further questions can be asked such as how does this influence the instrument’s repertoire and the musician’s performance?

To answer these questions, we will present data collected during three experiments in different cultural contexts and with musicians of different levels. Using acoustic equipment, we were able to measure the insufflated airflow, the pressure in the bag, the angle of the arm as well as make videos and record the sound. In order to complement our scientific data, we carried out an online questionnaire with 215 pipers, which allowed us to gather information on the perception of musicians and their subjective impressions on the control of their instrument. With acoustic measurements, qualitative data and an ethnomusicological framework, this research offers a multidimensional and interdisciplinary study of the control of the bagpipe’s bag.

Conference: First International Bulgarian Bagpipe Association Conference

Plovdiv Academy, Bulgaria

Paper Title: The bagpiper’s arm. Controlling the bag: a multidimensional study.

In this presentation, I endeavor to show how the bagpiper exerts control on his/her bag. Understanding this may enhance our comprehension of the importance of the arm in a musical context. Our main questions are: what role does the arm have in the control of the instrument? Is the bag controlled with musical intention? Leading from this, further questions can be asked such as how does this influence the instrument’s repertoire and the musician’s performance?

To answer these questions, we will present data collected during three experiments in different cultural contexts and with musicians of different levels. Using acoustic equipment, we were able to measure the insufflated airflow, the pressure in the bag, the angle of the arm as well as make videos and record the sound. In order to complement our scientific data, we carried out an online questionnaire with 215 pipers, which allowed us to gather information on the perception of musicians and their subjective impressions on the control of their instrument. With acoustic measurements, qualitative data and an ethnomusicological framework, this research offers a multidimensional and interdisciplinary study of the control of the bagpipe’s bag.

12-15 April 2017

Conference: Europe and post-Brexit Ethnomusicologies, British Forum for Ethnomusicology annual conference

Newcastle University, Newcastle, UK

Panel: Sounding Crisis and Precariousness on the Doorstep of Europe

Paper Title: Staying or Leaving? Greek and Cypriot Musicians in Post-Brexit London

Abstract

Almost every week for the past 18 months, there is news of yet another Greek or Cypriot musician going home, leaving London’s world music hub for good. Some choose to move back indefinitely; others commit to regular commutes for concerts in Europe or decide to try out a flexible arrangement between two or three countries. Often educated in the UK, these are musicians who are and have been actively involved in the diasporic, local, national and international music scenes for years. Paradoxically, many are leaving despite the fact that home is not synonymous with financial prosperity. Indeed, although Cyprus may be faring slightly better economically, Greece is still suffering from the aftermath of the crisis, enduring a seemingly unending and crippling austerity regime, forcing musicians to lower their financial standards and diversify their professional practice (Tsioulakis, forthcoming).

Focusing on individual voices in a post-Brexit environment, this paper explores the rationale behind London-based musicians’ decision making. Based on interviews carried out amongst musicians active in the world music scene, I identify the financial, ideological and practical elements on which post-Brexit Greek and Cypriot musicians base their reasoning. Through this, I wish to highlight the direct impact of Brexit and its on-going debate on the lives of creative international individuals as well the consequences for the cultural life of London and the UK.

Conference: Europe and post-Brexit Ethnomusicologies, British Forum for Ethnomusicology annual conference

Newcastle University, Newcastle, UK

Panel: Sounding Crisis and Precariousness on the Doorstep of Europe

Paper Title: Staying or Leaving? Greek and Cypriot Musicians in Post-Brexit London

Abstract

Almost every week for the past 18 months, there is news of yet another Greek or Cypriot musician going home, leaving London’s world music hub for good. Some choose to move back indefinitely; others commit to regular commutes for concerts in Europe or decide to try out a flexible arrangement between two or three countries. Often educated in the UK, these are musicians who are and have been actively involved in the diasporic, local, national and international music scenes for years. Paradoxically, many are leaving despite the fact that home is not synonymous with financial prosperity. Indeed, although Cyprus may be faring slightly better economically, Greece is still suffering from the aftermath of the crisis, enduring a seemingly unending and crippling austerity regime, forcing musicians to lower their financial standards and diversify their professional practice (Tsioulakis, forthcoming).

Focusing on individual voices in a post-Brexit environment, this paper explores the rationale behind London-based musicians’ decision making. Based on interviews carried out amongst musicians active in the world music scene, I identify the financial, ideological and practical elements on which post-Brexit Greek and Cypriot musicians base their reasoning. Through this, I wish to highlight the direct impact of Brexit and its on-going debate on the lives of creative international individuals as well the consequences for the cultural life of London and the UK.

3-4 April 2018

Invited speaker

Symposium: Music in culturally diverse societies: strategies, social engagement and significance

Sydney Conservatorium of Music, University of Sydney, Australia

This two-day symposium examines the musical activities of communities that have relatively discrete populations and do not form the majority ethnic or cultural group of the societies or countries in which they live.

The aim is (a) to promote a deeper and more nuanced understanding of how minority communities produce and maintain music-making within the context of culturally diverse societies such as Australia and the UK, and (b) thereby better understand the significance of musical activity within non-mainstream cultural groups while (c) taking a global perspective which enables a broad understanding of any common issues that emerge from nationally specific contexts.

The symposium brings together a diverse group of ethnomusicologists from the UK, Australia and elsewhere. The group includes the leading researchers on Australian Aboriginal music – almost all of whom are based at the University of Sydney. The symposium keynote address will be given by Dr Edward Herbst, a leading authority on Balinese music and Balinese musical repatriation. Discussions amongst this group of scholars aim to compare approaches to understanding and supporting minority musical creation, promoting learning from each other’s methodologies, practices, and insights. We anticipate that this will enable the development of more accurately targeted and well-informed applied research projects.

Invited speaker

Symposium: Music in culturally diverse societies: strategies, social engagement and significance

Sydney Conservatorium of Music, University of Sydney, Australia

This two-day symposium examines the musical activities of communities that have relatively discrete populations and do not form the majority ethnic or cultural group of the societies or countries in which they live.

The aim is (a) to promote a deeper and more nuanced understanding of how minority communities produce and maintain music-making within the context of culturally diverse societies such as Australia and the UK, and (b) thereby better understand the significance of musical activity within non-mainstream cultural groups while (c) taking a global perspective which enables a broad understanding of any common issues that emerge from nationally specific contexts.

The symposium brings together a diverse group of ethnomusicologists from the UK, Australia and elsewhere. The group includes the leading researchers on Australian Aboriginal music – almost all of whom are based at the University of Sydney. The symposium keynote address will be given by Dr Edward Herbst, a leading authority on Balinese music and Balinese musical repatriation. Discussions amongst this group of scholars aim to compare approaches to understanding and supporting minority musical creation, promoting learning from each other’s methodologies, practices, and insights. We anticipate that this will enable the development of more accurately targeted and well-informed applied research projects.

|

21 March 2018

Day of the Balearic Islands in Brussels Presentation for the Delegation of the Balearic Islands at the European Union Brussels, Belgium Ceremony: Ethnomusicologist assisting the gift of two Mallorcan instruments to the Musical Instrument Museum of Brussels (pictured) Presentation: Music of the Balearic Islands. An introduction With the contribution of musicians from Ibiza, Mallorca and Menorca Press: https://dbalears.cat/mon/2018/03/22/313201/les-balears-donen-dos-instruments-tradicionals-museu-instruments-musicals-brussel-les.html |

Joan Carles Munar playing the Majorcan cane flute given to the Musical Instruments Museum in Brussels. From left to right: Joan Carles Munar, Alexandra de Poorter (MIM director), Géry Dumoulin (Curator of popular music instruments), Isabel Busquets (Vice President of the Balearic Island Government), Antoni Vicencs (Deputy Director of the Centre Balears Europa in Brussels) and myself.

|

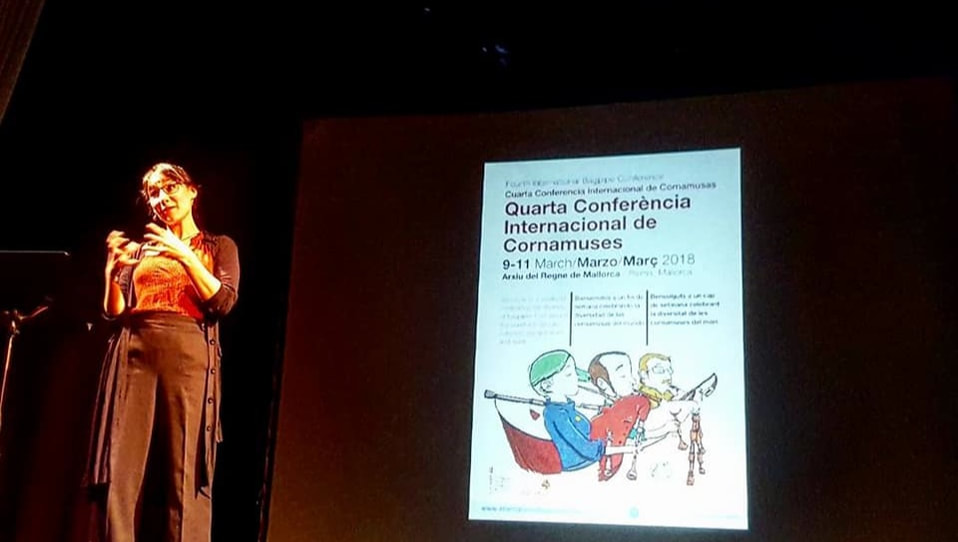

10 March 2018

Conference: International Bagpipe Conference

Mallorca, Spain

Title: The bagpiper’s arm. Controlling the bag: a multidimensional study.

Abstract

Conference: International Bagpipe Conference

Mallorca, Spain

Title: The bagpiper’s arm. Controlling the bag: a multidimensional study.

Abstract

|

Despite their many organological and esthetical differences, bagpipes are all played thanks to the movement of the arm on a bag, creating enough pressure to activate the reeds and produce sound. Unlike fingerings and melodic ornamentation, the musician’s arm technique is rarely discussed in bagpipe literature, nor is it particularly verbalized during a piper’s tuition. According to Simon McKerrell, ‘each player learns it individually and develops their own technique’ (2011). Despite this lack of verbalization, bagpipe experts seem to agree that the breathing technique and the bag are essential elements of their playing (Rice 2011, McKerrell 2011).

In this research, we endeavor to understand how the bagpiper exerts control on his/her bag. Understanding this may enhance our comprehension of the importance of the arm in a musical context. Our main questions are: what role does the arm have in the control of the instrument? Is the bag controlled with musical intention? Leading from this, further questions can be asked such as how does this influence the instrument’s repertoire and the musician’s performance? To answer these questions, we will present data collected during three experiments in different cultural contexts and with musicians of different levels. Using acoustic equipment, we were able to measure the insufflated airflow, the pressure in the bag, the angle of the arm as well as make videos and record the sound. In order to complement our scientific data, we carried out an online questionnaire with 215 pipers, which allowed us to gather information on the perception of musicians and their subjective impressions on the control of their instrument. With acoustic measurements, qualitative data and an ethnomusicological framework, this research offers a multidimensional and interdisciplinary study of the control of the bagpipe’s bag. |

19-23 February 2018

Visiting Lecturer

University of Malta, Malta

Lecture: The materiality of musical instruments

Visiting Lecturer

University of Malta, Malta

Lecture: The materiality of musical instruments

10 January 2018

Presentation for the town of Palma, Mallorca

Title: Les xeremies de Mallorca: un instrument social. Història, ressorgiment i cultura

Presentation for the town of Palma, Mallorca

Title: Les xeremies de Mallorca: un instrument social. Història, ressorgiment i cultura

|

Left: Xeremiers Pau i Candid playing at the opening of the presentation.

Above: Presenting International Bagpipe Conference 2018. |

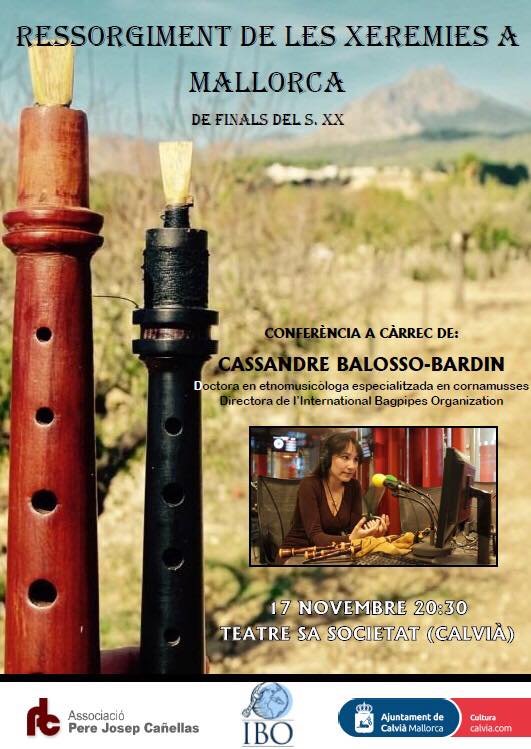

17 November 2017

Presentation at the Teatre sa Societat, Calvia, Mallorca

Title: Ressorgiment de les xeremies a Mallorca de finals del s. XX

Presentation at the Teatre sa Societat, Calvia, Mallorca

Title: Ressorgiment de les xeremies a Mallorca de finals del s. XX

13-19 July 2017

Conference: ICTM World conference

Irish World Academy of Music and Dance, University of Limerick, Ireland

Paper Title: Understanding an instrument: acoustics, movement and ethnomusicology.

Abstract

Time and time again, extremely talented musicians have pushed the boundaries of musical possibilities. Masters of their instruments to an extremely high level, they set themselves apart within a social and cultural context. This paper proposes to offer a different vision of the control a musician has over their instrument, fuelled both by the humanities and the sciences. An interdisciplinary research project gathering acousticians, engineers and ethnomusicologists focusing on musical gesture, acoustics and music (Geste-Acoustique-Musique) was inaugurated in Paris in 2015 within the Collegium Musicae. Close teamwork between acousticians from the Lutherie-Acoustique-Musique team (Institut d’Alembert, UPMC) and ethnomusicologists from Paris-Sorbonne Université led to a reflection on how collaborative research can inform the musical world, taking into account different actors such as instrument makers, musicians, composers and the audience.

This paper will first present one of the research projects as a case study, namely a musicians’s control of the bagpipe’s bag. Using visual but also acoustic and qualitative data collected over various measurement sessions both in the field and in a laboratory setting, the study will show how the control of an instrument is a two-way dialogue between the instrument (that imposes certain physical and acoustical limits on the musician) and the musician (who can adapt his control in order to bend the instrument to a musical thought) whilst part of an unfixed cultural context.

In a second part, we will illustrate how a closer understanding of the intimate relationship between a musician and his/her instrument can inform ethnomusicological reflection and lead to a broader knowledge of the musical world. This will lead to the presentation of an interdisciplinary reflection, proposing one of many frameworks possible for the study of musical instruments and its cultural, social and musical contexts.

Conference: ICTM World conference

Irish World Academy of Music and Dance, University of Limerick, Ireland

Paper Title: Understanding an instrument: acoustics, movement and ethnomusicology.

Abstract

Time and time again, extremely talented musicians have pushed the boundaries of musical possibilities. Masters of their instruments to an extremely high level, they set themselves apart within a social and cultural context. This paper proposes to offer a different vision of the control a musician has over their instrument, fuelled both by the humanities and the sciences. An interdisciplinary research project gathering acousticians, engineers and ethnomusicologists focusing on musical gesture, acoustics and music (Geste-Acoustique-Musique) was inaugurated in Paris in 2015 within the Collegium Musicae. Close teamwork between acousticians from the Lutherie-Acoustique-Musique team (Institut d’Alembert, UPMC) and ethnomusicologists from Paris-Sorbonne Université led to a reflection on how collaborative research can inform the musical world, taking into account different actors such as instrument makers, musicians, composers and the audience.

This paper will first present one of the research projects as a case study, namely a musicians’s control of the bagpipe’s bag. Using visual but also acoustic and qualitative data collected over various measurement sessions both in the field and in a laboratory setting, the study will show how the control of an instrument is a two-way dialogue between the instrument (that imposes certain physical and acoustical limits on the musician) and the musician (who can adapt his control in order to bend the instrument to a musical thought) whilst part of an unfixed cultural context.

In a second part, we will illustrate how a closer understanding of the intimate relationship between a musician and his/her instrument can inform ethnomusicological reflection and lead to a broader knowledge of the musical world. This will lead to the presentation of an interdisciplinary reflection, proposing one of many frameworks possible for the study of musical instruments and its cultural, social and musical contexts.

18-23 June 2017

Conference: International Symposium on Musical Acoustics

McGill University, Montreal, Canada

Paper Title: Music or Mechanics? Understanding the role of a bagpiper's arm.

Authors: Cassandre Balosso-Bardin, Augustin Ernoult, Patricio de la Cuadra, Ilya Franciosi, Benoit Fabre

Conference: International Symposium on Musical Acoustics

McGill University, Montreal, Canada

Paper Title: Music or Mechanics? Understanding the role of a bagpiper's arm.

Authors: Cassandre Balosso-Bardin, Augustin Ernoult, Patricio de la Cuadra, Ilya Franciosi, Benoit Fabre

Abstract

Despite their many organological and esthetical differences, bagpipes are all played thanks to the movement of the arm on a bag, creating enough pressure to activate the reeds and produce sound. Repertoires, scales and registers vary according to the instruments and their musical cultures, going from a fully chromatic scale over two octaves (such as the uilleann pipes from Ireland) to a diatonic scale within a range of a sixth (such as the Greek tsampouna or the Tunisian mizwid). Unlike fingerings and melodic ornamentation, the musician’s arm technique is rarely discussed in bagpipe literature, nor is it particularly verbalized during a piper’s tuition. According to Simon McKerrell, ‘each player learns it individually and develops their own technique’ [1]. Despite this lack of verbalization, bagpipe experts seem to agree that the breathing technique and the bag are essential elements of their playing [1],[2].

In this research, carried out during the Geste-Acoustique- Musique program (Sorbonne Universités, Paris), we endeavor to understand how the bagpiper exerts control on his/her bag. Understanding this may enhance our comprehension of the importance of the arm in a musical context. Our main questions are: what role does the arm have in the control of the instrument? Is the bag controlled with musical intention? Leading from this, further questions can be asked such as how does this influence the instrument’s repertoire and the musician’s performance?

To answer these questions, we will present data collected during three experiments in different cultural contexts and with musicians of different levels. Using acoustic equipment, we were able to measure the insufflated airflow, the pressure in the bag, the angle of the arm as well as make videos and record the sound. In order to complement our scientific data, we carried out an online questionnaire, which allowed us to gather information on the perception of musicians and their subjective impressions on the control of their instrument. With acoustic measurements, qualitative data and an ethnomusicological framework, this research offers a multidimensional and interdisciplinary study of the control of the bagpipe’s bag.

REFERENCES

[1] S. McKerrell, “Sound performing: sound aesthetics among competitive pipers,” in International review of the aesthetcs and sociology of music, 42/1. Croatian Musicological Society, 2011.

[2] T. Rice, “Evaluating artistry on the Bulgarian bagpipes,” in Ethnomusicological encounters with music and musicians. Farnham, Ashgate Publishing Limited, 2011.

Despite their many organological and esthetical differences, bagpipes are all played thanks to the movement of the arm on a bag, creating enough pressure to activate the reeds and produce sound. Repertoires, scales and registers vary according to the instruments and their musical cultures, going from a fully chromatic scale over two octaves (such as the uilleann pipes from Ireland) to a diatonic scale within a range of a sixth (such as the Greek tsampouna or the Tunisian mizwid). Unlike fingerings and melodic ornamentation, the musician’s arm technique is rarely discussed in bagpipe literature, nor is it particularly verbalized during a piper’s tuition. According to Simon McKerrell, ‘each player learns it individually and develops their own technique’ [1]. Despite this lack of verbalization, bagpipe experts seem to agree that the breathing technique and the bag are essential elements of their playing [1],[2].

In this research, carried out during the Geste-Acoustique- Musique program (Sorbonne Universités, Paris), we endeavor to understand how the bagpiper exerts control on his/her bag. Understanding this may enhance our comprehension of the importance of the arm in a musical context. Our main questions are: what role does the arm have in the control of the instrument? Is the bag controlled with musical intention? Leading from this, further questions can be asked such as how does this influence the instrument’s repertoire and the musician’s performance?

To answer these questions, we will present data collected during three experiments in different cultural contexts and with musicians of different levels. Using acoustic equipment, we were able to measure the insufflated airflow, the pressure in the bag, the angle of the arm as well as make videos and record the sound. In order to complement our scientific data, we carried out an online questionnaire, which allowed us to gather information on the perception of musicians and their subjective impressions on the control of their instrument. With acoustic measurements, qualitative data and an ethnomusicological framework, this research offers a multidimensional and interdisciplinary study of the control of the bagpipe’s bag.

REFERENCES

[1] S. McKerrell, “Sound performing: sound aesthetics among competitive pipers,” in International review of the aesthetcs and sociology of music, 42/1. Croatian Musicological Society, 2011.

[2] T. Rice, “Evaluating artistry on the Bulgarian bagpipes,” in Ethnomusicological encounters with music and musicians. Farnham, Ashgate Publishing Limited, 2011.

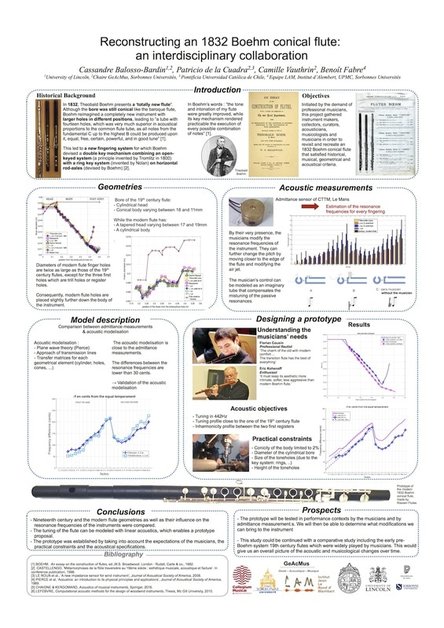

Paper Title: Reconstructing an 1832 Boehm conical flute: an interdisciplinary collaboration

Authors: Cassandre Balosso-Bardin, Patricio de la Cuadra, Camille Vauthrin, Benoit Fabre

Authors: Cassandre Balosso-Bardin, Patricio de la Cuadra, Camille Vauthrin, Benoit Fabre

Abstract

In 1832, flute-maker Theobald Boehm launches a brand new flute after conducting a series of acoustical experiments. The result was a flute with a conical bore, and a revolutionary key-system borrowing the best elements from different contemporary flute-makers to accommodate a complete modification of the instrument’s tone holes. However, he did not patent his 1832 model and “left it free for use and imitation” [1]. This means that despite its short life-span – by 1848 Boehm had already invented the modern flute with a cylindrical bore – and much rivalry from other manufacturers, the 1832 flute was built by many renowned makers until the first decades of the 20th century. Thus, although this instrument – that we named transition flute – was based on a specific model developed by Boehm, there was space for a wide variety of models. The lack of standardization means that when flautists play on transition flutes today, they are confronted to a wide variety of choice as each instrument is different.When commissioned by musicians to build a transition flute based on the 1832 conical model, the Flutes Roosen workshop was faced with a dilemma as the flutes all varied significantly. The following article shows how the geometrical and acoustic study of four transition flutes allowed us to propose a computer-generated model that simultaneously respected Boehm’s inventions and took into account the variety of models available. Rather than produce an exact copy of one instrument, we opted for recreating a new flute based on acoustic and geometrical measurements of different transition flutes and on Boehm’s desired improvements, detailed in his 1847 Essay on the construction of flutes [1].

REFERENCES

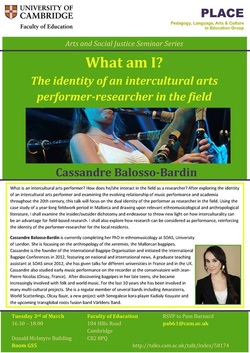

[1] T. Boehm, An essay on the construction of flutes. London: Rudall, Carte&co, 1832.